Bitter is Better: Cider Apples

Cider apples do not conform to the standards that most Americans

consider when thinking about apples – factors such as size, crispness,

and color are largely irrelevant to the quality of cider that a given

apple will produce.

What makes a cider apple?

There are three primary characteristics that determine how an apple

will be used in the cider making process: sweetness, or the quantity of

sugar present; sharpness, or how acidic it is; and bitterness, the

presence of compounds known as tannins which produce astringent and

bitter, “mouth puckering” flavors. The ratios between sugar, acid, and

tannin form the basis for the broad categories by which apples are

grouped – sweets, sharps, bitters, bittersweets, and bittersharps. While

a sweet apple might be the perfect thing for a pie or sliced with cheese,

it is the bitter tannins that create a complex, enjoyable alcoholic

beverage.

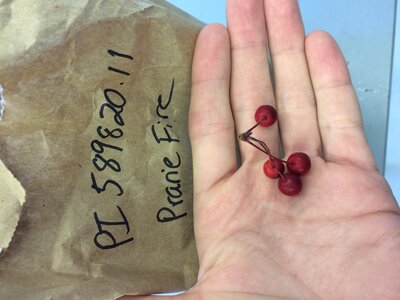

As can be seen in the apple cultivars shown here, the appearance of a cider apple is often not what we, as consumers, would consider a “good apple”. These photographs show cider apple varieties being grown at the Cornell University Agricultural Experiment Station research orchard in Ithaca, NY and the United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service’s apple germplasm repository in Geneva, NY. The “PI” numbers that can be seen with the apples on the right are assigned by the USDA to identify accessions in their collection of more than 3,000 unique apple genotypes.

Apple trees are an example of

extreme heterozygotes; that is, when

grown from seed an apple tree won’t

have the same characteristics as its

parent trees but instead will differ,

often radically. To preserve specific

traits, apples are propagated asexually

– by grafting.

The grafting process takes cuttings

from existing trees and attaches

them to other trees, such that the

cutting will grow on the new plant.

Most frequently this is done onto a

“rootstock” – a cloned root

system produced through asexual propagation – to make a

tree that will grow one specific variety

of apple. The rootstock determines many traits of the grafted tree, such as size, precocity (how early and often it will fruit), and resistance to diseases.